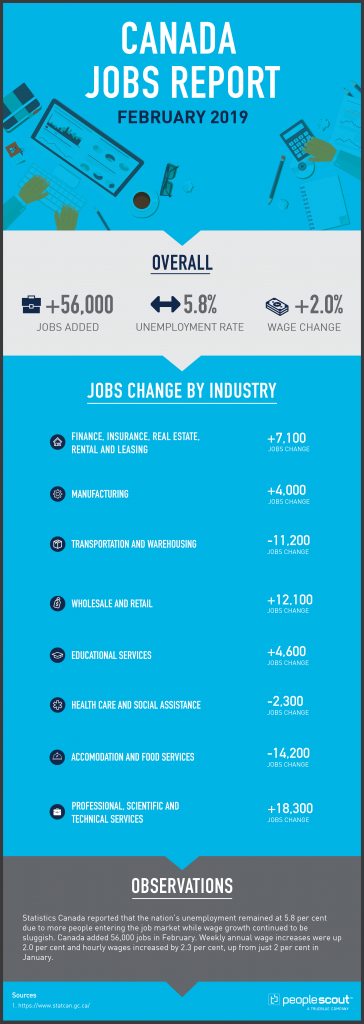

Statistics Canada reported that the nation’s unemployment remained at 5.8% due to more people entering the job market while wage growth continued to be sluggish. Canada added 56,000 jobs in February. Weekly annual wage increases were up 2.0% and hourly wages increased by 2.3%, up from just 2% in January.

The Numbers

56,000: The economy gained 56,000 jobs in February.

5.8%: The unemployment rate remained at 5.8%.

2.0%: Weekly wages increased 2.0% over the last year.

The Good

The strong February figures follow an even bigger gain of 66,800 jobs in January. This is the best two-month increase in the job market since 2012. The unemployment rate was unchanged is because more Canadians joined the labour force. In the past 12 months, total employment grew by 369,000 or 2.0%, reflecting increases in both full-time (+266,000) and part-time (+103,000) work.

While the gains are still modest, wage growth began to pick up in February. Annual hourly and weekly wages increased by 0.5 percentage points over January. Economists welcomed the positive wage growth and the resilient job market which appeared to shrug off signals for concern in other parts of the economy:

“The weak economic data that closed out 2018 and soft momentum heading into this year has not yet had any impact on the jobs numbers,” Toronto-Dominion Bank economist Brian DePratto said. ” Labour markets didn’t get the memo.”

Ontario was the big winner again in February with an increase of 59,000 full-time positions. On a year-over-year basis, employment in the province increased by 2.7% or 192,000.

The Bad

The good news for Ontario in February was the exception since the job numbers for most of the rest of Canada remained flat or showed modest fluctuations. In Alberta, where the economy is heavily influenced by the energy sector, the unemployment rate increased. The CBC reported that the rate increase was spurred by an increase of those looking for work.

“Alberta’s employment level was mostly unchanged from January and last February, but the agency says the number of people looking for work has increased, pushing the provincial unemployment rate up to 7.3%. Calgary’s unemployment rate for February is even worse at 7.6%, up 0.3% from January. Edmonton’s unemployment rate also rose to 7.0% from 6.4% in January.”

The contrast to Ontario’s unemployment rate of 5.7% is not limited to Alberta. Prince Edward Island’s unemployment rate stands at 10.3% and New Brunswick’s at 8.5%. These maritime provinces have struggled with high unemployment in recent years contributing to a lop-sided jobs market which favors the richer and more populous provinces.

The Unknown

The Globe and Mail notes that one constant in the monthly jobs report numbers is that they appear to consistently defy analyst expectation.

“What’s an easy way to trip up an economist? Ask one to forecast Canadian job growth…Derek Holt, head of capital markets economics at Bank of Nova Scotia, pointed out the chronic shortfall in estimates after January’s report. Since the end of 2015, the economy had added nearly 900,000 jobs, as measured by the net change in employed persons. Economists called for 325,000 positions, or less than 40% of the total, based on the monthly consensus forecast of those surveyed by Bloomberg….

Economists have long struggled to pin down job gains. To some degree, that’s defensible. The LFS is often derided as a ‘random number generator,’ largely because the monthly change in employment comes with a hefty margin of error, typically around 29,500. For some perspective, since 2000 the Canadian economy has added an average of 18,600 jobs per month, or substantially lower than the margin of error.

Put another way, we typically don’t know whether Canada truly added or lost jobs from one month to the next. December provides a good example. The LFS said a net 8,700 jobs were created that month. But here’s another way of describing what happened: the true figure may have fallen between a gain of 37,200 jobs and a loss of 21,600 positions, after taking into account the margin of error. Even then, there’s a chance the true figure fell outside that range.

For economists, their forecasts have hit a particularly rough patch. Consider that from 2000 through 2015, the consensus amounted to 58% of the total number of jobs created during that period, versus 37% since then.

So, what’s going on? Douglas Porter, chief economist at BMO Nesbitt Burns, points to population gains. In a February research note, he noted that Canada’s population aged 15-plus increased by 432,100 in January from a year earlier, the largest 12-month increase in 43 years of records…

There’s also another factor at play: job growth, per the LFS, might simply be playing catch-up. Statscan has multiple measures of employment, including the payroll survey of employers, which many economists consider a more reliable gauge of job growth. Since the end of 2015, cumulative job growth was fairly similar between the surveys, before the LFS started to lag in 2018. January’s outsize gain went a long way to narrowing the gap.”