Stats NZ released the March Quarter Labour Market Report which reported that the unemployment fell to 4.2% in the first three months of the year, from 4.3% in the final quarter of 2018. Economists expected a jobless rate of 4.3%. The number of people unemployed declined at a faster rate than the number of people in the labour force. The result was the unemployment rate falling close to its 10-year low of 4.0%, set in mid-2018. The labour market underutilisation rate was 11.3% in the first quarter, the lowest rate since the December 2008 quarter.

The Numbers

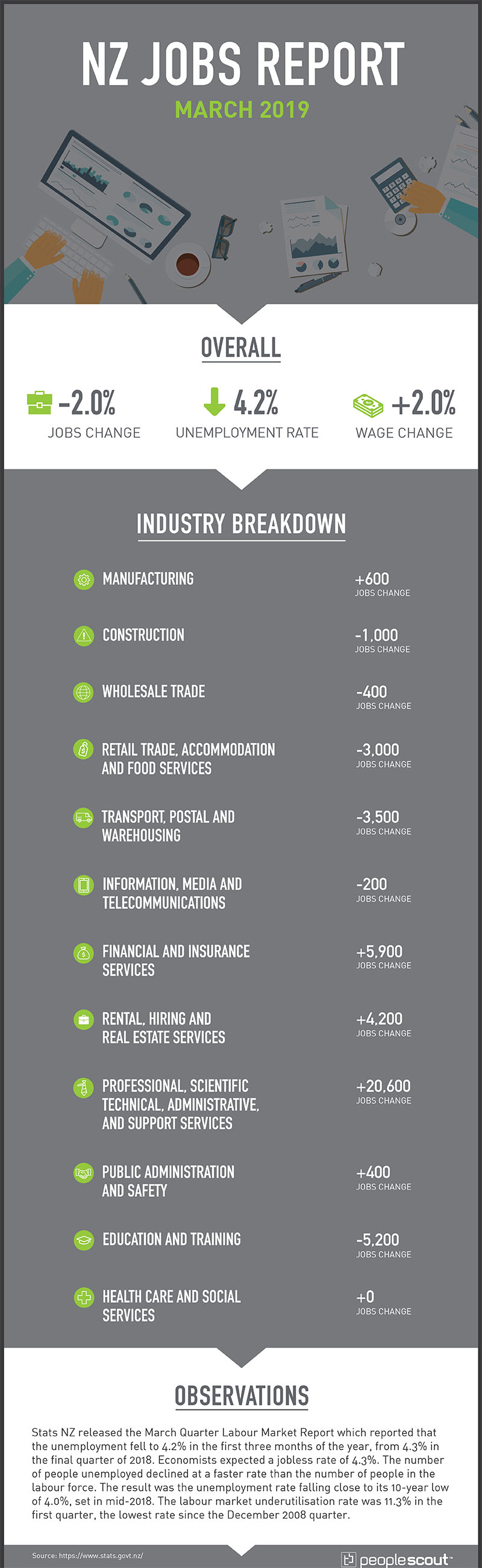

-4,000: The economy lost 4,000 jobs in the first quarter of 2019.

4.2%: The unemployment rate fell to 4.2%.

2.0%: Overall wages increased 2.0% over the last year.

The Good

Stats NZ released the March Quarter Labour Market Report which reported that the unemployment fell to 4.2% in the first three months of the year, from 4.3% in the final quarter of 2018 and beating analyst expectations. The number of unemployed declined at a faster rate than the number of people in the labour force. As a result, the unemployment rate fell close to its 10-year low of 4.0% set last year. Compared to last year, 38,200 more people were employed, an increase of 1.5% – comprised of 25,400 women and 12,800 men.

The labour market underutilisation rate was 11.3% in the first quarter, the lowest rate since the fourth quarter of 2008. Underutilisation provides a broad gauge of untapped capacity in New Zealand’s labour market. In the first quarter, the number of people underutilised decreased by 14,000 to 324,000. There were 8,000 fewer underutilised women and 6,000 fewer underutilised men.

The Bad

For the first time in more than four years, the New Zealand economy lost jobs. In addition, the number of jobs created over the past year was slightly more than half the rate of the previous year. Coupled together, these figures indicate a weakening and possible end of the steady job market growth seen in recent years. The slowing job market may have implications for the economy as a whole as Stats NZ Senior Manager Jason Attewell noted:

“Generally, employment growth tends to lag broader economic growth by about three months, New Zealand has seen a softening of economic growth as measured by gross domestic product over the last six months, and we now are seeing that softening come through the employment rate.”

Wage growth is also frustratingly low, even in a tight labour market, as the New Zealand Herald reports:

“ANZ economists have picked unemployment to remain flat at 4.3% although they acknowledge risks in either direction depending on the flow through from business confidence.

Regardless, it looks set to remain at levels which economists often describe technically as ‘full employment.’

That has led to some debate as to why wage growth has remained so subdued. In fact, it has been a major source of economic uncertainty globally as well as locally.

‘More significant government-related increases are likely to come later in the year,’ Westpac’s Gordon says.

‘Wage growth tends to lag the broader economic cycle. Even if the demand for new workers is fading, there appears to be enough accumulated pressure in the labour market to support a pickup in wage growth over the next couple of years.’

ASB’s Mark Smith described this year as a pivotal one for wage trends.

‘Our view had been that stretched labour market capacity and the boost to wages provided by minimum wage increases and moves towards more Fair Pay agreements would be sufficient to trigger a generalised firming in overall wages,’ he wrote.

‘The failure to date for wages to come to the party has challenged that view.’”

The Unknown

What will the impact of new technology be on New Zealand’s future workforce? The New Zealand government asked the Productivity Commission to conduct an inquiry into technological change and the future of work. The result is an issues paper that presents four possible scenarios as presented in CIO Magazine:

- More Tech More Jobs: Technology adoption accelerates in this scenario, and the technologies adopted create more jobs than they replace. Both capital and labour productivity rise in this scenario, perhaps substantially.

- More Tech and Fewer Jobs: This scenario, in common with the first one, is driven by accelerating technology adoption. However, it differs in that the technology adopted is, overall, labour replacing. Capital productivity rises substantially in this scenario, as firms increasingly adopt productivity-enhancing technologies. Labour productivity might also rise, as lower-skilled roles are increasingly automated. An expected consequence of this combination of drivers is widespread unemployment.

- Stagnation: In this scenario, the pace of technological adoption slows. This could be due to declining innovation, as technological bottlenecks prove harder to overcome than expected. Alternatively, slower change could occur as technology adoption by firms slows – perhaps because newer technologies are less productivity enhancing for firms than those of the past.

- Steady As: In this scenario, the technological drivers of labour market change over the next one-to-two decades stay within the bounds of New Zealand experience over the past one-to-two decades. This future offers ongoing change, according to the paper, but the rate of that change is roughly that which New Zealanders are familiar with.

Regardless of how or whether these scenarios take place in New Zealand’s economic future, New Zealanders appear to be unconcerned about losing their jobs to technology. The New Zealand Herald reports that a recent Massey University study found 87.5% of respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics or algorithms could take my job.”